13 October 2025

5 min read

Going beyond the botanical in Kew’s Persian collections

Learn about the social and cultural histories tucked away in our Persian collections, as displayed in our new exhibition in the Library & Archives Reading Room.

Our Library & Archives hold one the world’s largest and most significant botanical collections. But did you know that they contain another world of cultural, linguistic and social histories that go beyond the botanical?

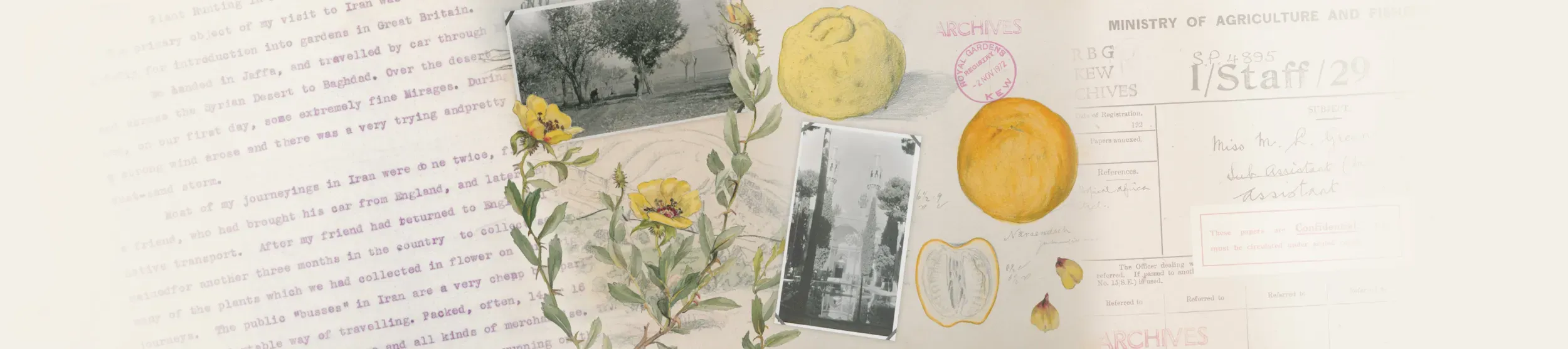

Our Library & Archives Reading Room display ‘Persia Reimagined: From Herbarium to Heritage’ explores these stories in our Persian materials through notebooks, journals, publications and botanical illustrations.

Why does Kew Gardens hold Persian materials?

You may be wondering why we hold these materials in the first place. Our collections frequently correspond with British political and economic interests: for example, we hold a lot of materials relating to colonial India.

While Persia was never a British colony, its proximity to colonial India made the British government determined to maintain a level of influence and trade there.

Throughout this blog, the name Persia – denoting the region and culture – has been used in favour of Iran to reflect the context of these records and their original content. Persia, (derived from Persis Greek for Pars/Fars), was long used in the West, though locals always called the country Īrān (ایران).

In 1935, the country’s ruler Reza Shah requested foreign governments adopt Iran to reflect national identity. Later, in 1959, his son and successor Mohammad Reza Shah allowed both Persia and Iran to be used interchangeably in cultural contexts.

What's in the Persian collections of Kew Gardens?

This exhibition has been co-curated with previous MA placement student Shabnam Balouch, who has been volunteering with our Archives team for over two years.

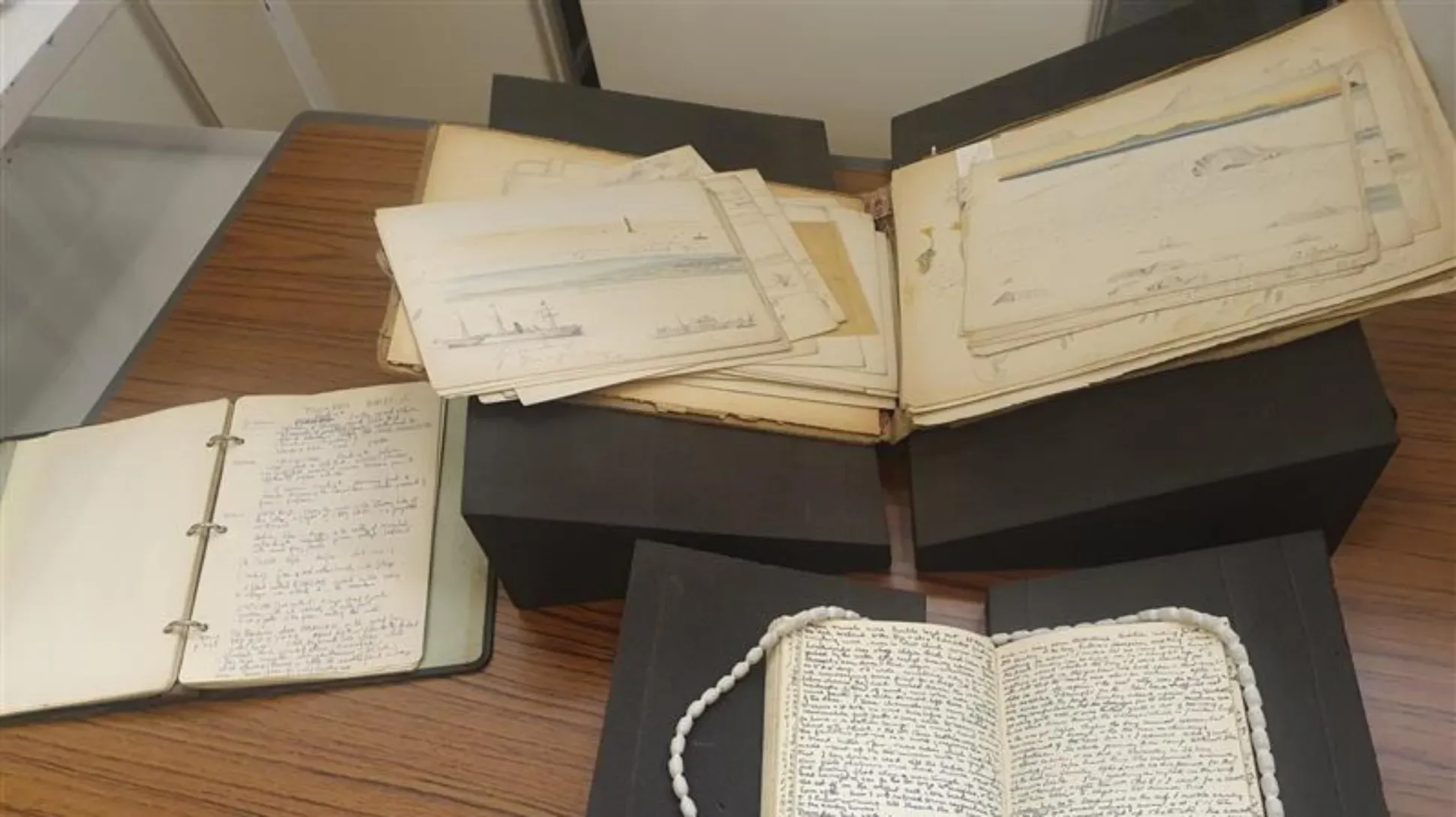

As part of this placement, she studied the papers of Edward Kent Balls (1894-1984), whose collection of diaries and collecting notebooks form the basis of this exhibition. Here, she recounts her first impressions of working with the collections:

When I first encountered the Persian collections at Kew, what struck me most was how much more they contained than botanical notes and plant specimens. In Edward K Balls’ diaries and collecting notebooks, I began looking for plants, but quickly found myself absorbed in the voices, landscapes, and everyday details woven through his writing.

His records captured not just specimens, but also moments of hospitality, descriptions of gardens, and traces of conversations with the people he met. It was clear from the start that these were not just scientific documents, but cultural ones.

Exploring Balls’ diaries led me deeper into the collections, searching for more and uncovering hidden gems that held far more than botanical information. Within these papers, sketchbooks, and photographs, I began to see a broader story of Persia emerge. One that revealed cultural practices, linguistic nuances, and personal encounters, often preserved almost by accident. That journey of discovery highlighted the importance of re-examining these archives, not only as scientific records but also as rich sources of social and cultural history.

It was clear that these areas of our collections deserved a deeper dive and a bigger spotlight.

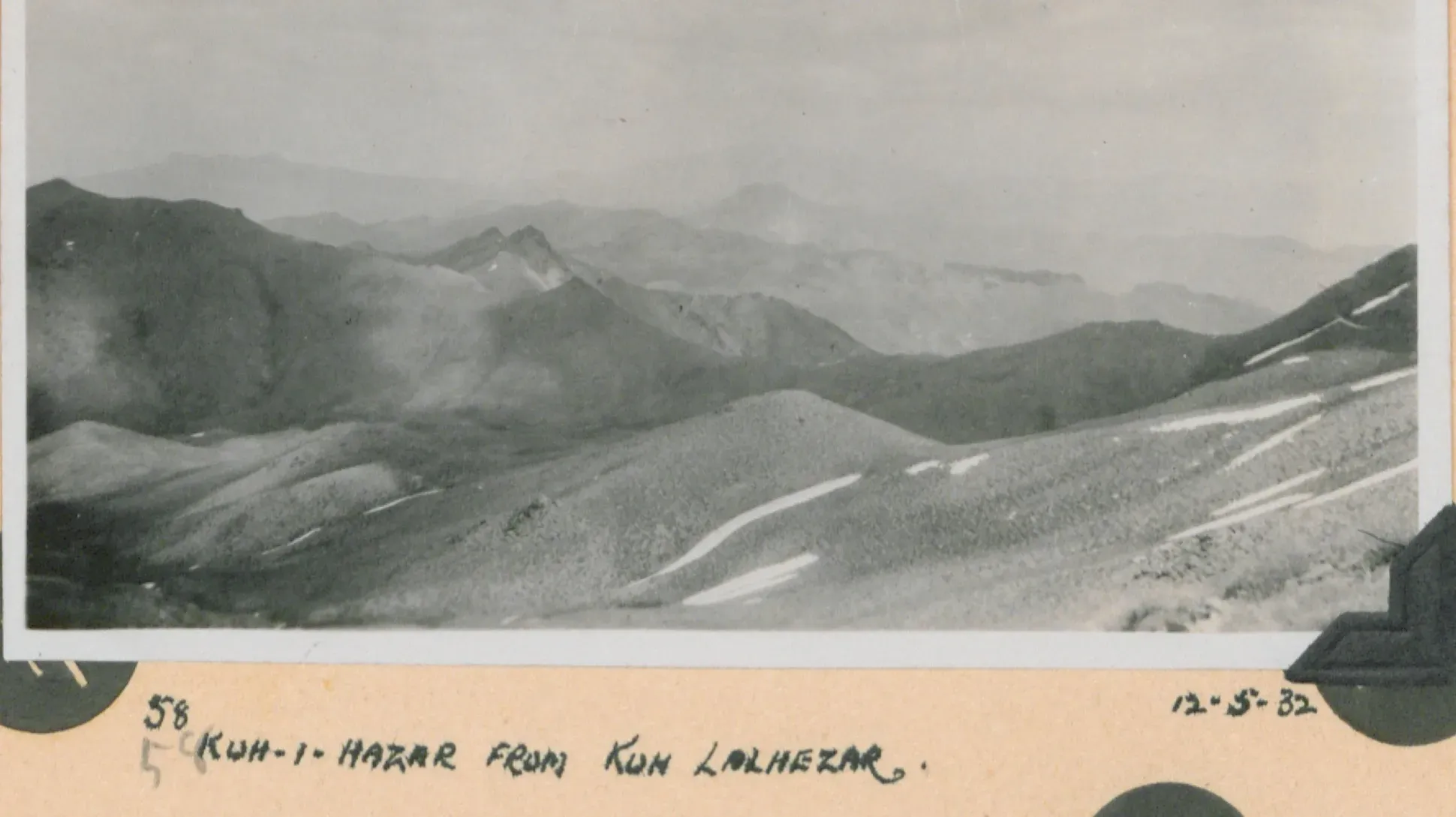

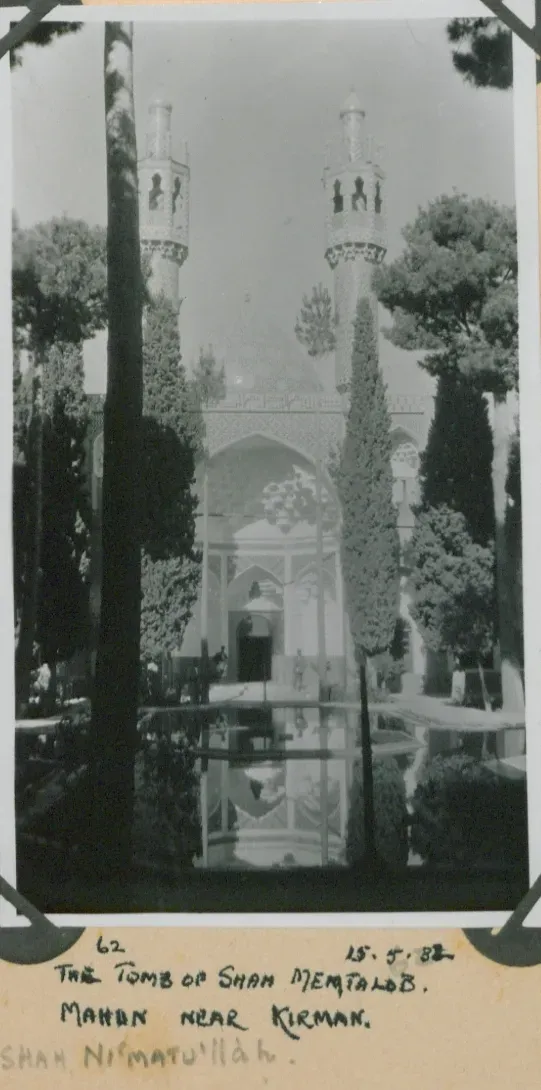

A favourite item from the Balls collection which features in the exhibition is his photo album of an expedition to Persia in 1932. While he was travelling primarily for plant collecting, he recorded a lot more through his photography. He captured landscapes, architectures, and the more personal: his hosts and guides and their gardens and customs.

The collections of Otto Stapf

The exhibition also features another earlier collector, Otto Stapf (1857-1933), who would go on to work at Kew as Keeper of the Herbarium. A couple of decades prior to his move to England, however, Stapf travelled to Persia and recorded his impressions in a collection of plant collecting papers, journals, and another feature in our exhibition: his sketchbook.

His visual impressions aren’t only of plants encountered but also look at the Persian landscape more widely, with charming details such as a small donkey or horse grazing in the foreground.

![A sketch from Stapf’s sketchbook, showing a ruin at “Kasrun” [Kazerun, Fars province]. A native Austrian, Stapf’s annotations are primarily in German. STA/1/2 A drawing of a Persian landscape with a small donkey in the foreground](webp/kazerun-fars-province-stapf.jpg170c.webp?itok=YqTGauFf)

Persian collections at the British Library

In preparation for this exhibition, Shabnam and I had the privilege of visiting William Monk, Content Specialist Archivist at the British Library who showed us some fantastic items from their collections, including a large vegetational map of the Turko-Persian border.

We have even been able to feature a facsimile from the Curzon collection, a photograph taken by Lt A A Crookshank, accessible here: 'South Persia'. Photographer: Lt. A. A. Crookshank (Curzon Collection) | Qatar Digital Library.

William has offered some insight into the British Library’s collections and how they connect to botanical history:

To the British colonial Government of India, Persia was a key piece on an imperial chessboard. For this reason, many sources on Britain’s long history of commercial, political, diplomatic, and military interventions in Persia (dating from the 18th century until the independence of India in 1947) which formed the backdrop to botanic collecting, are held in the British Library’s India Office Records.

Many of these have been digitised as part of the British Library-Qatar Foundation Partnership, and can be freely accessed anywhere in the world on the Qatar Digital Library. This digitisation project makes sources on these histories more accessible to the people of Iran and the region whom they continue to affect. The photograph featured in this exhibition comes from the private papers of Lord Curzon, one of the most significant figures in Anglo-Persian relations.

The exhibition takes the visitor through stories around food, drink, languages, and travellers’ recollections of conversations with locals. A perfect conclusion to the exhibition are items from Shabnam Balouch’s personal collection, a real visual treat!

This display is only a small snippet into this world of our collections and with added cultural and historical contextualisation from our co-curator, we hope to bring these materials closer to our visitors and spark some conversations and discovery.

In order to make our collections more accessible to a wider audience, we will also be running workshops in which participants will be invited to create artistic responses to the materials. We are grateful to the British Institute of Persian Studies for funding this workshop and we will be hosting an online talk with BIPS in December – please sign up and come along if you’d like to find out more. We will also run workshops with Persian communities, funded by The National Archives.