9 September 2025

5 min read

The date palm that defied domestication - could it hold the key to resilient crops?

Could a “wild” date palm help us rethink what it means to domesticate a crop - and even offer a lifeline for agriculture in a changing climate?

For centuries, humans have shaped plants to meet our needs: sweeter fruits, larger harvests, greater resistance to pests. But domestication often comes at a cost. Many of our staple crops have become dependent on human care - unable to thrive without irrigation, fertilisers, or protection from disease.

The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) is one such crop: deeply valued across arid regions of North Africa and the Middle East, its fruits enjoyed across the world, yet the plant remains heavily reliant on human intervention.

So what happens when some of these domesticated palms escape cultivation and go it alone? What if they not only survive, but thrive for centuries in harsh, dry conditions without help from humans?

If a plant like this has managed to adapt to extreme environments on its own, it may have developed unique survival traits - tolerance to drought, resistance to disease, or the ability to grow in poor soils.

Nature’s hidden innovations

Traits like these, evolved outside the controlled conditions of farming, could be invaluable if reintroduced into the cultivated gene pool. In a warming world, where food security is increasingly uncertain, tapping into this kind of “wild” resilience could be the key to future-proofing our crops.

That’s exactly what we see in the Cape Verde date palm (Phoenix atlantica), a palm growing wild across parts of the Cape Verde islands.

So - is it a distinct species in its own right, shaped by isolation and evolution? Or is it a feral offshoot of the cultivated date palm, with roots in ancient human trade routes and adaptation to life untended?

This is more than a question of taxonomy. The answer could offer crucial insights for the future of food - especially as we search for crops that can withstand increasing drought and climate extremes.

A curious case: Investigating the Cape Verde date palm

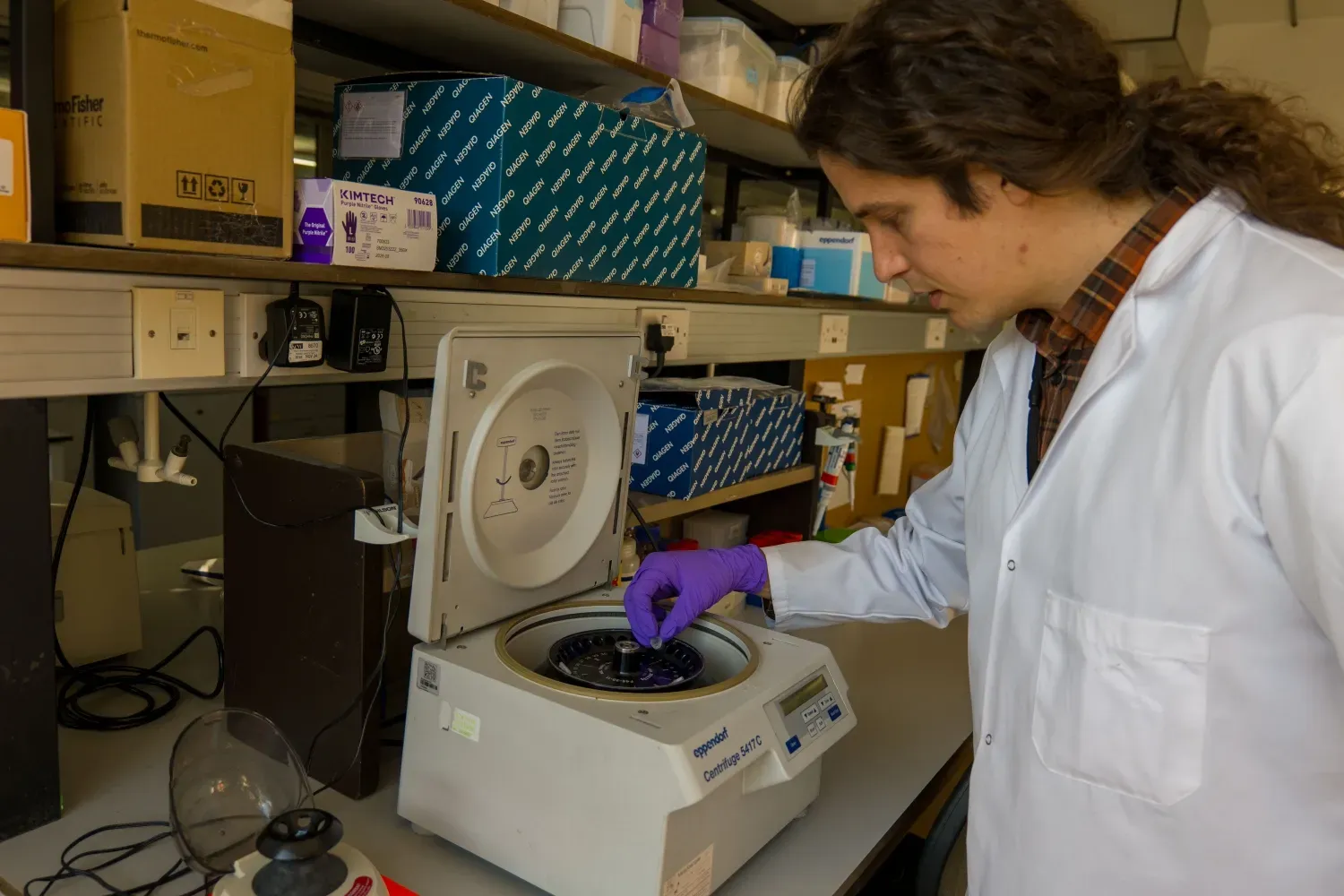

In our latest research, published in Plants, People, Planet, we investigated the origins and adaptations of P. atlantica through genetic analysis and seed morphology - piecing together its evolutionary story and uncovering potential clues for breeding more resilient date palms.

What if this wild-growing plant holds the key to improving drought tolerance and disease resistance in one of the world’s most important arid-climate crops?

The concept of feralisation - when domesticated crops survive and propagate in the wild without human care - plays a central role in our research. Cultivated date palms (P. dactylifera) typically require irrigation, pest control, and laborious manual fertilisation to achieve optimal yields. However, as mentioned, their feral counterparts, like P. atlantica, have adapted to survive without these interventions.

Our top three discoveries

My interest in this study stems from a fascination with the intersection of biological evolution and human selection. As I delved into the genetic makeup of the Cape Verde date palm, three key discoveries stood out:

- A Single Ancestral Escape: Our genetic analysis showed that P. atlantica is monophyletic, meaning all individuals in the species evolved from a small population of cultivated date palms that escaped.

- Genetic and Morphological Overlap with Domesticated Date Palms: P. atlantica’s genetic diversity overlaps substantially - but not entirely - with North African date palm varieties, and its seeds are elongated, a trait associated with domestication. This provides strong evidence for its feral origins while highlighting its uniqueness.

- Progenitor-Derivative Speciation: P. atlantica and P. dactylifera form a rare evolutionary system where a species emerges from an ancestor that still exists. However, it is genetically distinct enough to suggest it has been evolving independently for some time. This raises fundamental questions: at what point do we classify it as something distinct, and what role could its genetic uniqueness play in agriculture?

So, to put it simply, our research shows that the Cape Verde date palm (Phoenix atlantica) is not a distinct wild species, but a feral offshoot of the cultivated date palm that escaped human cultivation and adapted to life in the wild.

Yet, over time, it has evolved enough to develop its own genetic distinctiveness which might just help safeguard one of the world’s most important arid-climate crops.

Unlocking answers with Kew’s Herbarium specimens

Our dried plant specimens at Kew (now available online for free) played a crucial role in this research. We were able to analyse historical material, including the type specimen of P. atlantica, using modern genomic techniques.

Because herbarium specimens are expertly identified - and type specimens serve as the official reference for a species - they provide an essential baseline for comparing genetic and morphological features across species.

With specimens preserved for decades or even centuries, they offer a unique window into the past that can now be studied in new ways as technology advances.

What’s next? The remaining questions

Our findings raise an important taxonomic question: should P. atlantica remain classified as a separate species, or should it be considered a subspecies of the cultivated date palm? This decision carries implications not just for scientific classification but also for conservation and local communities who use the plant as a source of animal forage, construction materials, handicrafts and shade.

We are now working to engage with researchers from the country to understand the cultural and ecological significance of P. atlantica. Meanwhile, its potential for crop breeding remains an exciting avenue for future research.

As climate change threatens food production, integrating P. atlantica into breeding programs could provide new solutions for improving the resilience of date palms against drought and disease.

Let’s connect

I am keen to connect with other scientists interested in the taxonomic treatment of P. atlantica or anything else about my work. If that’s you, do reach out and contact me (you can find my contact details on my profile page) and it will be a pleasure to chat.

Further reading:

To learn more about the genetic make up of the Cape Verde date palm and challenges surrounding its conservation, check out this other study led by scientists from the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria of (Canary Islands, Spain).

Acknowledgements:

This research wouldn’t have been possible without the guidance and expertise of my supervisor Sidonie Bellot, whose mentorship has been instrumental throughout, and the close collaboration of Oscar Alejandro Pérez-Escobar, whose insights and support were key in shaping both the scientific questions and the direction of the study.

I would also like to thank Paris Herbarium (MNHN) for access to the P. atlantica specimens and seeds.