29 October 2025

6 min read

From Seeds to Skylarks

A story of seed-based UK landscape restoration within the Changing Chalk Partnership

Watching our steps, we drag a tape measure through a prickly, uneven landscape. Then, kneeling down, we get lost in a miniature world.

We’re here to find out what species are growing in selected areas of a restoration experiment.

Are those tiny black “teeth” on the edges of the leaf? It must be common knapweed, Centaurea nigra. The slightly twisted blades of quaking grass, Briza media, allow me to recognise it and make a mark by its name on the data sheet.

These are just a few of the species we’re most eager to observe, because they are typically found in one of Britain’s most interesting habitats - chalk grassland.

Chalk grassland in the UK

Looking closely at chalk grassland, a simple one square metre patch of tiny, nibbled green things becomes disentangled into as many as 40 different species of plant, each one with its distinctive flowers, aromas and/or uses.

You may also see or hear other specialized organisms such as the beautiful Chalk Hill blue butterfly and farmland birds such as the melodious skylark thriving in this biodiverse environment.

The species that make their home in chalk grassland are adapted to the low nutrient, grazed habitat which emerged on the chalky hills of Southern England around 6,000 years ago, when humans removed woodland and started farming sheep. Grazing animals are still essential in order for the ecosystem to remain intact today.

Though this ecosystem has deep roots in human history, it has only taken a few recent decades for humans themselves to drastically threaten it through intensive agriculture (e.g. the overuse of fertilizers) and other changes in land use. Today, only 4% of the South Downs are occupied by some of the remaining fragments of chalk grassland.

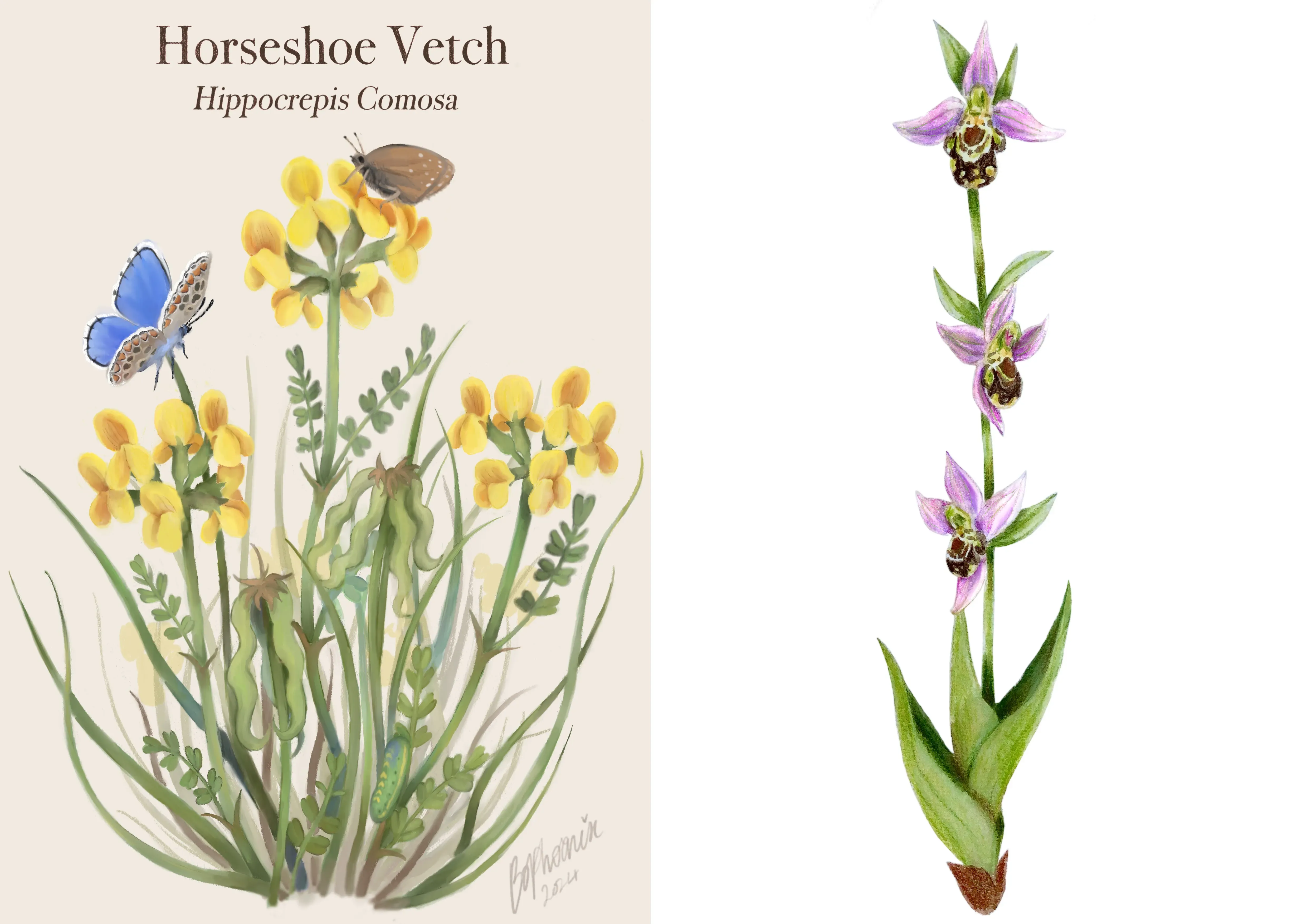

With so little left, let’s name and celebrate a few chalk grassland plants in this gallery.

How do we protect Britain’s remaining chalk grassland?

In order to restore and celebrate this ecosystem at a landscape level, we at Kew are playing a role in a large partnership of organizations that’s come together to deliver the Changing Chalk Project.

Supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and led by the National Trust, the Changing Chalk Project connects people, nature and heritage across the eastern South Downs. Some of the 18 Changing Chalk projects include protecting the rare wart-biter bush-cricket (led by Buglife), a Farm School for primary school children (led by Brighton and Hove City Council) and recruiting “Monument Mentors” to manage ancient monuments (led by the National Trust).

As part of the Changing Chalk Project, our team at Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank, led by Ted Chapman, is studying how we can restore chalk grassland using seeds at two different sites on the South Downs.

Back in 2022, we removed patches of scrub from the landscape as part of the new study. In November of that year, we sowed portions of these areas with different locally sourced chalk grassland seed mixes. Some of these seeds had been taken from our own collection held at the Millennium Seed Bank.

We each walked up and down a few portions of the slopes, spreading the precious seed evenly on the ground on a bright autumn day.

Testing the power of landscape recovery

Since then, seedlings have emerged and grazing animals such as sheep, cattle and ponies have been visiting the sites and playing their important role by munching away at the plants.

Every summer we return to the sites to monitor what species are germinating and growing in each treatment. The palatable species contained in some of our seed mixes had been selected to particularly attract grazing animals, with the idea that the grazing pressure will suppress the re-growth of scrub. This should favour the return of chalk grassland.

In time, the knowledge we build from these tests will be turned into technical resources and guidance for anyone involved in chalk grassland restoration to use – so if that’s you, keep an eye out! It would be exciting to see our studies applied to restore these valuable ecosystems across the South Downs and beyond.

Art and science meet: connections through Changing Chalk

Working on the Changing Chalk Project has also been a great opportunity to connect with other organizations and people. I was able to connect with artists Pauline Rutter and Bo Rutter, who worked on their own Changing Chalk–funded project entitled: “From Collections to Connections”.

While Archival artist Pauline Rutter has been researching, writing poetry, and organising community walks with young people and families of Black, Asian, and mixed heritage as well as other minority ethnic groups, Bo Rutter has been producing illustrations of chalk grassland species. This has included an illustration of a bee orchid (Orphys apifera) which was partly inspired by illustrations held in Kew’s library and archives collection. I was honoured to join their end of project celebrations and share the story of our Millennium Seed Bank UK team there.

The similarities between artists and scientists struck me. We are all closely observing the tiny beauty hidden in the hilly landscape, kneeling down to look at the details of the plants and gathering their stories, be it in the form of data or of poetry. Only thanks to a partnership like this with different perspectives can we truly recover an ecosystem and its connection to people, rooted in history.

What can you do to help chalk grassland?

If you’ve read this and want to see chalk grassland for yourself and get involved, here’s some ideas for you.

Go and explore, find your local chalk grassland, and volunteer with one of the many Changing Chalk groups and activities.

While you’re out and about on the Downs, notice the diversity of living things, look out for flowers, aromas and wildlife. You might even hear a skylark repeatedly warbling above you!

Visit the Millennium Seed Bank at Wakehurst to learn more about seed conservation and use. There is a parterre in front of the Millennium Seed Bank where you can find chalk grassland habitat and learn more about it.

With that, I leave you with this poem by Pauline Rutter, who leaves me longing to return to this special landscape once again.

Up on Mill Hill

Come walk, take a stroll on Shoreham’s Mill Hill

Where there’s Greater Knapweed and Ragwort still,

Open your eyes perhaps you will see,

A beetle, a butterfly or maybe a bee.

Is a Kestrel up high, in majestic flight?

Is the Skylark calling until it is night?

These, the chalk grasslands of your South Downs,

Just up and along from our Sussex towns.

What is the chalk that’s right under our feet?

Dazzlingly white in the summer heat?

Tiny plankton skeletons, billions and more

Did you know they use to be on the sea floor?

Then the tectonic plates, yes the land pushed and eased

Until up rose the hills and see what they achieved

There’s insects and birds, flowers and grass

And all because people, cattle and sheep came to pass

Then the bustling collectors of rare butterflies

Intensive farming and pesticides

And now, all is fragile and in need of great care

Rewilding and restoring of what else should be here

The rangers can tell you, the internet too.

I wonder if there’s something we all could do.

So next time you visit, wander round spend some time

Gaze out to the wind farm and remember this rhyme.

Acknowledgements

Changing Chalk is a multi-partner project connecting people, nature and heritage across the eastern South Downs. It is restoring lost habitats, bringing histories to life, and offering new experiences in the outdoors. Led by the National Trust, Changing Chalk is supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund, thanks to National Lottery players, and The Linbury Trust.

Thanks to Bo Rutter and Pauline Rutter for sharing their works, of which you can view more via the links attached to their names.