15 September 2025

4 min read

Fruits, roots and more: uncovering Kew’s carpological collection

From hidden treasures to hands-on discoveries, Lucy Horton shares what she learned during her year as an Undergraduate Science Intern at Kew, shining a light on the fascinating world of the carpological collection.

Deep within Kew’s Herbarium lies a collection brimming with potential: the carpological collection. Home to more than 53,000 specimens of fruits, roots, bulbs, tubers, and other plant materials too large or intricate to be to be mounted on a standard herbarium sheet, it represents a treasure trove of botanical diversity.

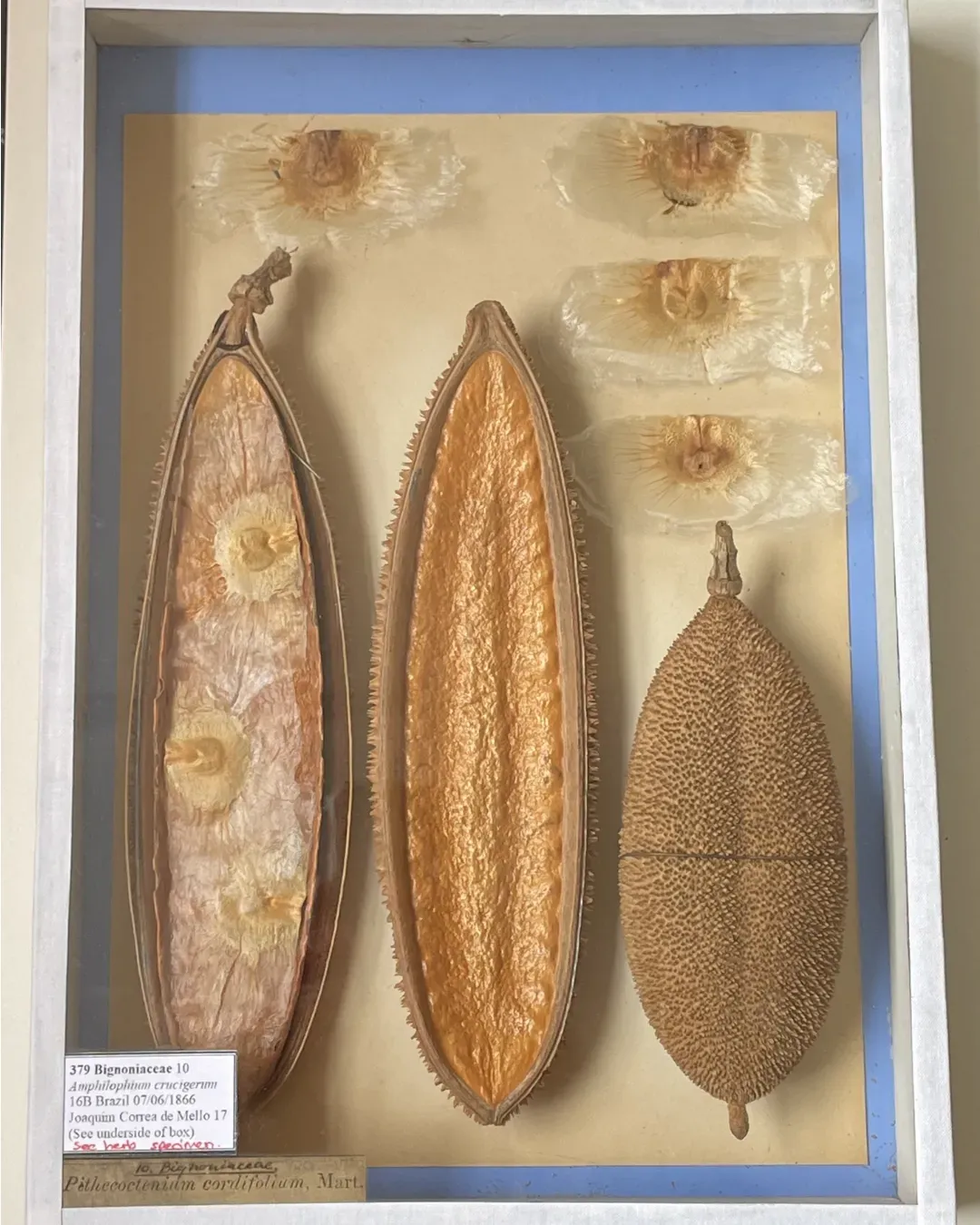

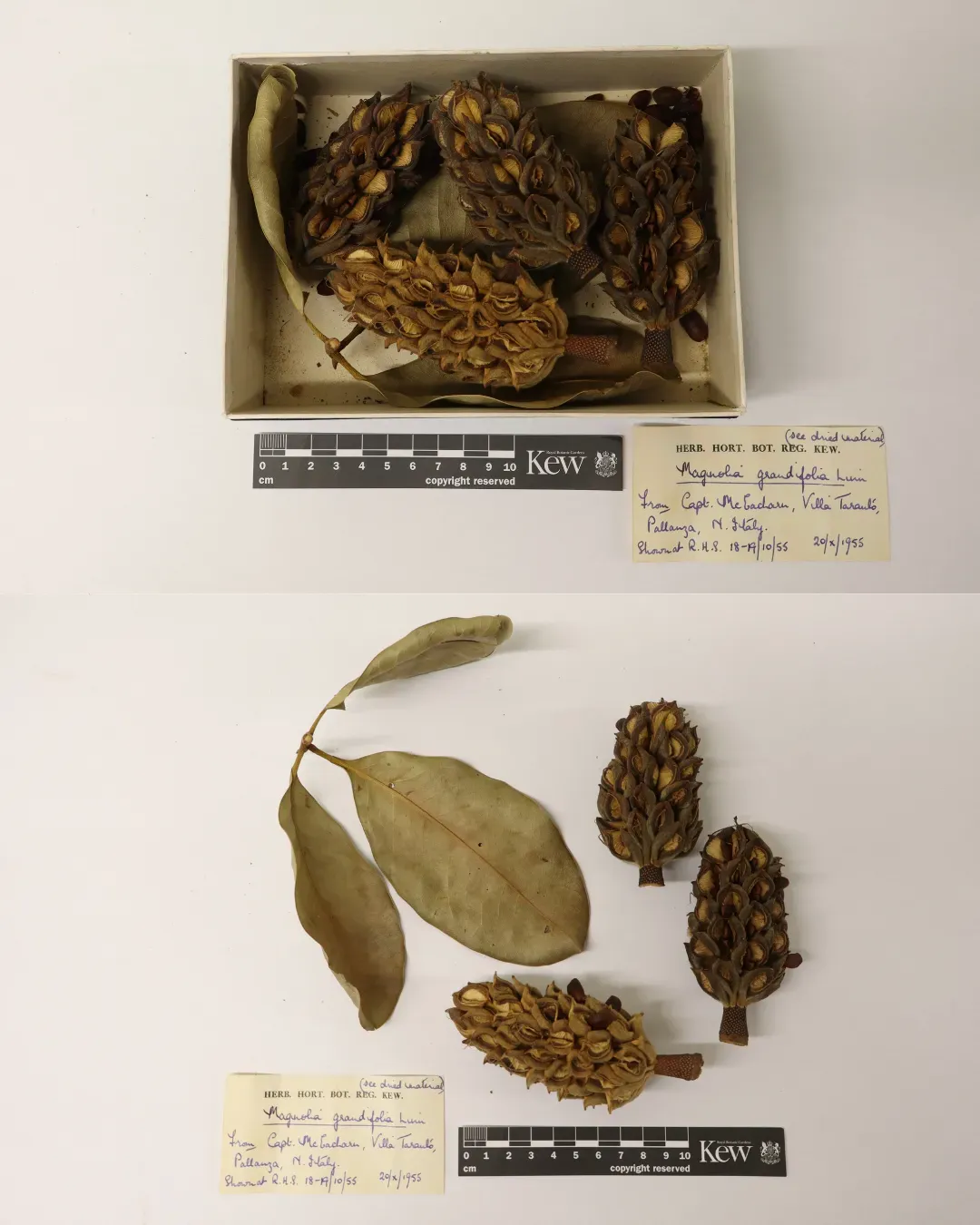

Each specimen rests in its own glass-topped archival box, carefully arranged in drawers and cupboards like a botanical time capsule, full of possibilities for research, education, and even art.

Breathing new life into the collection

Over the past year, Lucy Horton has worked alongside Senior Curator Botanist Clare Drinkell and the herbarium curation team to bring renewed attention to this vast collection. Her internship focused on updating plant names, cross-referencing specimens with their associated herbarium sheets, and improving the way the collection is stored and accessed.

“Before starting at Kew, I knew very little about the role of a herbarium in conservation,” Lucy reflects. “I now understand that the taxonomic and curation work done here is an incredible tool for identifying and classifying the world’s flora.”

Specimens with stories to tell

The collection gets its name from ‘carpology,’ the study of fruits - derived from the Greek ‘karpos,’ meaning fruit. While there are many fruits, the collection is also home to a variety of other things too!

“The carpological collection is home to a wealth of miraculous and marvellous specimens” says Lucy, “It is a great solution for keeping parts of plants that are less easy to press and mount, or that have complex 3D structures.”

Inside the collection are parasitic flowers like the iconic Hydnora and Rafflesia; the massive fruits of the Madagascan baobab trees; tiny coffee berries, and even some cacti.

Some specimens, like the riverweed family Podostemaceae, even remain attached to the rocks they grew on, preserving their ecological story for researchers to explore.

Why curation matters – and the challenges along the way

While other herbaria also store fruits and parts of specimens that are too large to be mounted, Kew’s carpological collection is unique as it is the only collection on such a large scale, with material spanning across the globe from many different plant families.

But updating and conserving a collection of this scale isn’t easy. With over 6.4 million herbarium sheets at Kew, ensuring that the carpological collection stays accurate and accessible, alongside these takes time and precision. When scientists update plant names on herbarium sheets, for instance, these three-dimensional specimens can sometimes be forgotten - creating gaps that Lucy’s work helped to close.

For Lucy, the internship was as much about problem-solving as it was about plants.

“The 3D nature of the collection makes handling and curating it very different to working with standard herbarium sheets,” says Lucy, “Every specimen is so different, the way it is boxed, stored, and should be handled varies on a case-by-case basis.”

Some specimens have also required conservation work and re-boxing, and a large part of the job has been ensuring that specimens are stored in an easy-to-understand sequence (usually by family, areas and alphabetically by species), with the least risk of damage.

Accurate curation means researchers can locate specimens quickly, trust the information they contain, and use the collection to advance scientific understanding.

So, what’s the draw of a well curated carpological collection?

For one, it bridges the worlds of science, history, and art. Although fruits aren’t often a key focus for species descriptions, some specimens are linked to ‘Type’ herbarium sheets, the official specimens used when a plant species was first described, making them invaluable for taxonomic research and reference.

The collection’s diversity makes it a valuable resource for researchers worldwide. “One of the highlights of my placement was meeting researchers from Moscow State University who visited Kew to sample specimens,” Lucy recalls. “It was a wonderful chance to see the collection contributing to real scientific studies.”

“But this collection isn’t just about identifying species,” Lucy notes, “its curation provides the specimens and data we need to explore wider research questions and tackle global challenges, from conservation priorities to understanding how plants respond to changing environments.”

Beyond its scientific value, the collection also holds aesthetic and creative appeal.

“The carpological collection is full of character!”, Lucy notes “From opening the glass topped boxes, unfurling the labels - some with handwritten notes, and handling three-dimensional specimens from across the world, the collection really can inspire art!”

Local artist Johanna Bolton, for example, drew on the intricate fruits of the Gardenia genus for a sculpture series in 2018.

Looking Ahead

As interest in the collection grows, so does its potential. With growing enthusiasm for its preservation and hopes for future scope for digitisation, the curation work done to update the carpological collection is becoming increasingly important and has highlighted the potential for this collection to be used more for botanical research.

From conservation efforts to creative projects, this hidden gem at Kew promises to keep inspiring curiosity for years to come.